The Quiet Revolution: How Christianity Became a Cornerstone of Modern Korean Society

From tent revivals to towering megachurches, Christianity has quietly reshaped Korean society over the past century. This article traces the faith’s rise, its cultural tensions, and its spiritual legacy in a country still navigating tradition, modernity, and global influence.

A Quiet Yet Explosive Shift

It began not with a bang, but with a whisper.

In the years following the devastation of the Korean War, this peninsula was scarred, divided, and desperate for hope. Amidst the rubble, a movement stirred—tents turned into sanctuaries, whispered prayers echoed in basements, and borrowed hymnbooks passed between hands calloused by conflict.

Christianity in Korea did not emerge through dominance or cultural inheritance. It arrived humbly, carried by missionaries, embraced by students, and nourished by the suffering of those who sought something more enduring than ideology or empire.

Today, over 30% of South Koreans identify as Christian, with Seoul alone hosting more megachurches than any other city on earth. It is a staggering transformation by any historical measure. But the real story lies not in statistics or steeples—it lies in how faith has quietly shaped Korean identity, public discourse, and even its global image.

This is the quiet revolution—how Christianity became, and remains, a spiritual cornerstone of modern Korean society.

The Historical Roots: Missionaries, Martyrs, and Modernization

Long before Seoul lit up with neon crosses, the seeds of Korean Christianity were planted in soil soaked with struggle.

The Arrival of Protestant Missionaries to Korea in the Late 1800s

The first Protestant missionaries arrived in the late 19th century, most notably Horace G. Underwood and Henry Appenzeller in 1885. But it was the groundwork laid by early Catholic converts and persecuted believers under the Joseon dynasty that prepared the way. The early Korean church was not simply imported—it was forged in blood.

Christianity’s Role in the March 1st Movement

During the early 20th century, Christians played a vital role in resisting Japanese occupation. Churches became gathering places not only for worship but for political awakening. In fact, many of the signatories of the March 1st Independence Declaration of 1919 were Christians—an early sign that the Korean church would be more than just a spiritual refuge. It was also a force for justice.

In the post-war decades, Christianity surged as Korea rebuilt itself. The alignment of Western aid, education systems, and missionary-led hospitals and schools helped make Christianity synonymous with modernization, education, and opportunity.

But this was no mere cultural export. The gospel took root in a uniquely Korean way—infused with passion, resilience, and community. Revival meetings swept through the countryside. Churches sprouted in every urban district. Faith became not just personal—it was national.

“What makes the Korean church unique,” writes theologian Samuel Lee, “is not simply its size, but its depth of suffering and breadth of vision.”

And it is here that we begin to see how a quiet revolution—unseen by much of the world—was underway.

The Rise of the Megachurch: A Double-Edged Sword

If revival lit the fire, structure built the furnace.

As South Korea industrialized in the 1970s and 80s, cities swelled, families fragmented, and the national psyche shifted from survival to success. It was in this crucible that the Korean megachurch emerged—not merely as a place of worship, but as a cultural institution.

Nowhere is this more visible than at Yoido Full Gospel Church in Seoul. Founded in 1958 by Pastor David Yonggi Cho, Yoido began in a tent with five people. Today, it claims over 800,000 members, making it the largest Pentecostal congregation in the world. To some, it is a modern miracle. To others, a case study in the dangers of unchecked religious scale.

Defining a Korean Megachurch: More Than Just Size

The Korean megachurch model—defined by high-capacity buildings, multi-campus systems, extensive social programming, and charismatic leadership—became a template imitated across Asia and beyond. Churches like Sarang, Onnuri, and SaRang Jeil drew tens of thousands weekly, with ministries for every demographic: children, youth, singles, retirees, even North Korean defectors.

But size, as Scripture reminds us, is not always synonymous with sanctity.

Critics have raised legitimate concerns:

- Leadership centralization often results in scandal and succession crises.

- Prosperity theology—the teaching that faith guarantees financial success—has taken root in some corners, distorting the gospel.

- Spiritual consumerism, fed by concert-style worship and sermon branding, can erode the sacred simplicity of discipleship.

Community, Charity, and the Flip Side of Scale

As a retired pastor, I’ve sat with young men who left such churches burned out, feeling more like numbers than members. And yet, I’ve also met widows who found life-saving community in those very pews. The truth, as with many movements of God, lies in the tension.

We must resist the urge to either romanticize or demonize the megachurch. Instead, we should ask: What spiritual hungers did they answer? And what disciplines must they recover?

As we reflect on the rise of Korea’s church giants, we do well to remember that Christ did not come to build brands, but to shepherd souls.

Pop Culture Meets the Cross

For centuries, the church has wrestled with its place in culture—when to embrace, when to resist, and when to redeem. Korea is no exception. But here, the collision of Christianity and modern pop culture has taken on a uniquely vibrant—and sometimes puzzling—form.

Walk the streets of Seoul, and you’ll see it: neon crosses glowing above high-rises, Christian bookstores nestled between skincare boutiques, and worship music echoing from cafés where students sip iced Americanos and study scripture side by side with economics.

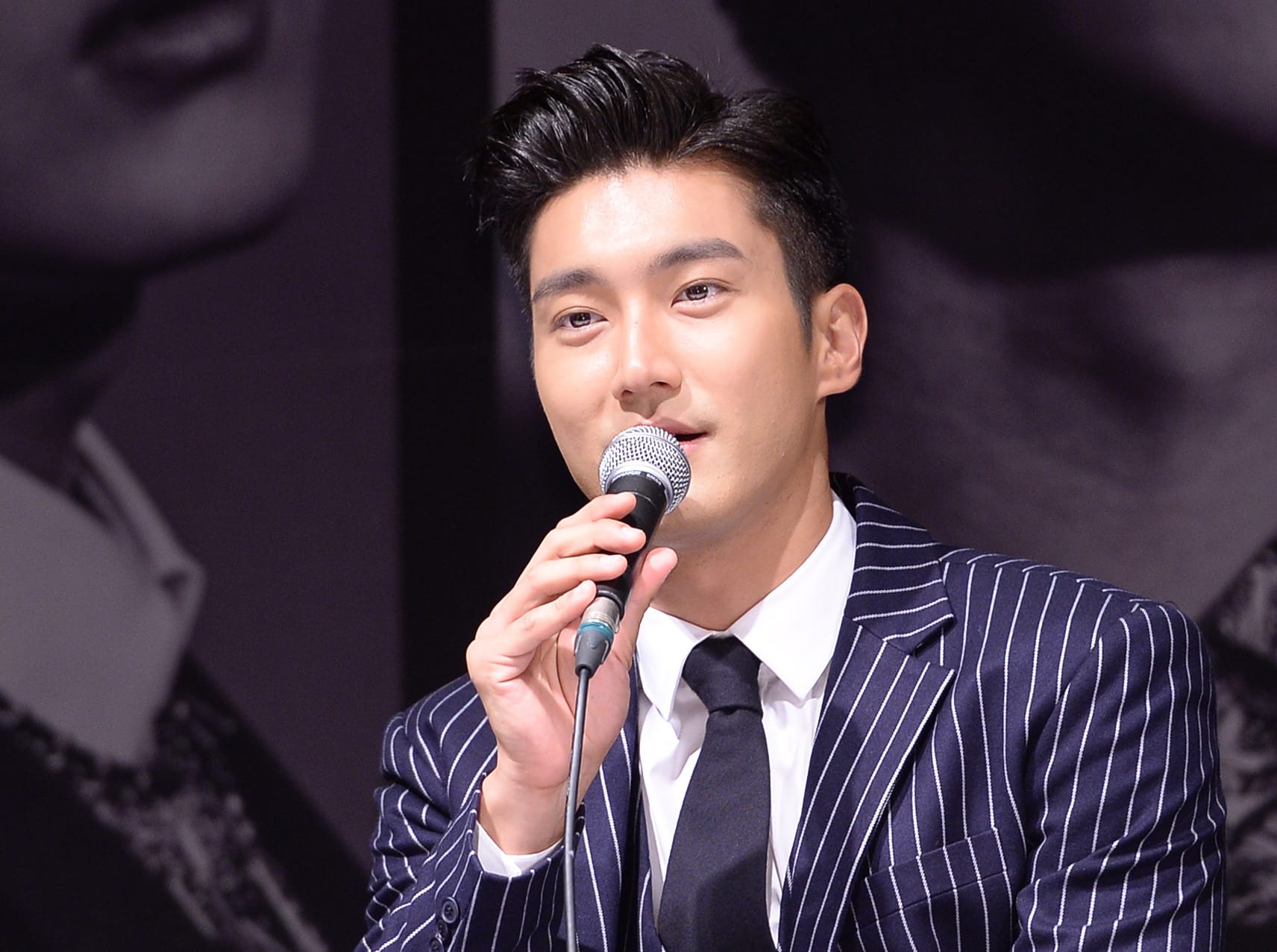

K-Pop Idols Who Publicly Identify as Christian

Some of the nation’s biggest pop culture figures openly profess their Christian faith. K-pop idols like Choi Siwon (Super Junior) and Taeyang (BIGBANG) speak publicly about their relationship with God. These aren't mere passing mentions—some even cite faith as central to their identity. While critics may question the depth of such expressions, it’s clear that Christianity holds a legitimate seat at Korea’s cultural table.

“The Gospel here doesn’t whisper—it sings in neon.”

YouTube, Gospel Music, and Faith in the Algorithm Age

The rise of Christian YouTubers, TikTok evangelists, and podcasting pastors has blurred the line between pulpit and platform. Some ministries now livestream in 4K with full production crews. Others operate as one-person teams broadcasting nightly devotionals from smartphones. While some elders may bristle at these changes, the method—if not always the message—is evolving.

Even K-dramas have begun exploring religious themes with nuance. Series like “Hospital Playlist” present characters whose faith is quietly integral, not performative or caricatured. It's a far cry from earlier portrayals that often painted clergy as either comical or corrupt.

As the Apostle Paul once addressed the philosophers of Athens using their own language and references, so too must the church in Korea learn to speak in the vernacular of its generation—without diluting the truth it carries.

Still, the tension remains. Does the digital stage deepen devotion or distract from it? Can spectacle and sincerity coexist?

In my years teaching young believers, I’ve seen both outcomes. One student discovered the gospel through a Christian drama shared by a friend. Another fell into shallow teaching and confusion through an influencer who quoted more slogans than Scripture.

As we move forward, discernment—not dismissal—must guide us.

The question is not whether Christ can be found in Korean pop culture. The question is whether we, His followers, will recognize Him there when He appears in unfamiliar form.

Theological Divide: Conservative Roots vs. Emerging Progressivism

Every living faith tradition carries within it both a memory and a momentum—a reverence for what has been handed down, and a wrestling with what the Spirit might be saying now.

Korean Christianity is no different. Beneath its unity of cross and creed lies a growing tension: one between its conservative foundations and an emerging wave of progressive theological inquiry.

Historically, the Korean church—particularly within Protestantism—has leaned heavily evangelical and theologically conservative. Influenced by American missionaries in the mid-20th century, many seminaries emphasized biblical inerrancy, literal interpretation, and traditional gender roles. For decades, these frameworks offered clarity and order amid societal upheaval.

But times, as they always do, are changing.

The Rise of Progressive Theology Among Korean Youth

Younger generations—both Korean and foreign—are asking hard questions:

- What does faithfulness look like in a society grappling with LGBTQ+ inclusion?

- Should women still be denied pastoral authority in churches that claim equality before God?

- How do we reconcile a gospel of peace with a national church history often entwined with political power?

And yet, even within these questions, I hear echoes of faithful longing—not rebellion, but reformation.

I’ve attended conferences where Korean theologians passionately debate these topics not to tear down the church, but to purify it. I’ve also met young believers—fluent in Scripture—who lament feeling spiritually homeless in churches where silence on justice issues feels louder than any sermon.

It’s tempting for some in the older guard to dismiss these concerns as cultural drift. But the wise shepherd knows: when sheep cry out, we don’t lecture them. We listen.

"Test everything," the Apostle Paul writes. "Hold fast to what is good." (1 Thess. 5:21)

We must remember: orthodoxy is not afraid of questions. It is forged by them.

At the same time, caution must be exercised. A progressive theology that becomes untethered from the authority of Scripture drifts not into freedom—but into fog. The answer, I believe, lies not in polarization but in humble pursuit. A posture that says: I may not agree, but I will not assume. I will not condemn before I understand.

Korea’s theological future is not yet written. But the way forward, as always, begins not in debate halls or Twitter threads, but at the foot of the cross.

The Foreigner’s Pew: How Korean Churches Embrace (or Overlook) Expats

On any given Sunday in Seoul, if you wander into a large church, you might notice a side room with a flickering projector screen and a few rows of plastic chairs. This is often the “foreigner service.” Sometimes it’s vibrant, with dedicated pastoral care and cultural sensitivity. Other times, it feels more like a footnote to the main event upstairs.

And yet, week after week, the pews are filled.

South Korea is home to over two million foreign residents, and a growing number of them are seeking spiritual community—some as English teachers or factory workers, others as students, diplomats, or missionaries themselves. And yet, many churches remain unprepared or unequipped to fully welcome them.

I've spoken with expats who wept with gratitude after being offered communion in their native tongue—and with others who left in silence after feeling invisible in a room full of believers.

Churches Known for Welcoming Expats and Migrants

To be fair, some Korean churches have made extraordinary efforts:

- Onnuri Church (Seoul) offers multilingual services and hosts international fellowships.

- Jubilee Church, planted by missionaries, has become a spiritual home for hundreds of expats navigating life and faith in Korea.

- Smaller congregations across the country are beginning to integrate interpretation services and multicultural ministries, often led by second-generation Korean-Americans or overseas-trained pastors.

But challenges remain.

Language is the most obvious barrier, but beneath that lie deeper currents: cultural expectations around worship, prayer styles, leadership roles, and even fellowship etiquette. What feels reverent to one may feel rigid to another. What feels warm to one may feel intrusive to another.

Hospitality is not merely the act of opening doors, but of opening hearts—and that takes time, intention, and mutual humility.

As a former pastor to both Korean nationals and foreign believers, I can say with conviction: the Korean church is at a crossroads. It can either treat expat ministry as a courtesy, or as a calling.

The nations have come to Korea’s doorstep—not just for work or study, but often in search of meaning, healing, and connection. To ignore that divine opportunity is to miss one of the most Spirit-filled frontiers of modern ministry.

Let us remember: in the eyes of the kingdom, there is no “foreigner’s pew.” Only one body, one Spirit, one hope to which we are called.

A Legacy Still Being Written

Christianity in Korea did not arrive with fanfare. It did not conquer with power or political favor. It endured—through persecution, poverty, and partition. And from that endurance, it grew roots deeper than many expected.

Today, South Korea sends more missionaries per capita than any other nation except the United States. Its churches support hospitals, orphanages, shelters, and seminaries across the globe. It is not uncommon for a rural village in Africa or Southeast Asia to be home to a clinic built by a Korean congregation.

And yet, for all its external impact, the most powerful legacy of Korean Christianity may lie within.

Within the quiet prayers of an ajumma who prays every morning at 5am.

Within the whispered hallelujahs of migrant workers worshipping in borrowed basements.

Within the soft click of subway earbuds, playing sermons between commutes.

Within the tensions—the questions, the reforms, the reimaginings—that prove a faith is still alive and growing.

As I reflect on the decades I’ve spent here—teaching, preaching, learning—I find myself continually humbled. Not by the grandeur of Korea’s churches, but by their grit. Their resilience. Their capacity to adapt without abandoning the cross.

"Not by might, nor by power, but by my Spirit," says the Lord of hosts. (Zechariah 4:6)

The story of Christianity in Korea is far from over. Its next chapter will not be written solely in seminaries or sanctuaries—but in living rooms, coffee shops, youth retreats, and foreigner fellowships. It will be written in Korean, in English, in Tagalog, in Urdu, in prayer.

And perhaps, if we listen closely, we’ll hear that same quiet revolution still unfolding—not with thunder, but with testimony.

Richard E. Landon

Retired pastor, missions historian, and contributing writer for the Faith & Family series.

More from this author →

Subscribe to the Faith & Family Newsletter

Get weekly stories, reflections, and insights on faith, family, and expat life in Korea — straight to your inbox.

Join the Community